Did you know that many common products are classified as dangerous goods, even though they don’t appear hazardous at first glance? For instance, that bottle of perfume or aftershave you’re shipping is highly flammable. Likewise, everyday items like nail polish also fall under flammable categories, and aerosols such as hairspray or deodorant contain compressed gases. Furthermore, nearly all electronic devices with lithium batteries – from mobile phones and laptops to power tools – pose a fire risk if damaged or improperly handled. These seemingly innocent items are just a few examples of the complexities businesses face when shipping goods.

In Australia, this landscape is made even more intricate by a multi-layered regulatory oversight. Different authorities oversee dangerous goods depending on the transport mode: the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) for air freight, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) for sea freight, and various state or territory agencies for road and rail transport. This complex web of governance adds another significant layer of compliance for businesses, demanding meticulous attention to detail.

Given this intricate environment, the consequences of mismanaging dangerous goods can be severe. Imagine hefty fines that cripple your budget, significant legal penalties that damage your reputation, and unavoidable transport delays that frustrate your customers. Beyond these immediate business impacts, mishandling dangerous goods can lead to devastating environmental damage or, most tragically, serious safety incidents like fires or explosions. Therefore, for any business involved in shipping dangerous goods, understanding hazardous goods classification is essential.

What Exactly Are Dangerous Goods?

At its core, dangerous goods refers to any substance or article that pose a risk during transportation. Moreover, this risk may affect health, safety, property, or the environment due to the item’s chemical or physical properties. This broad definition encompasses a surprisingly vast array of items.

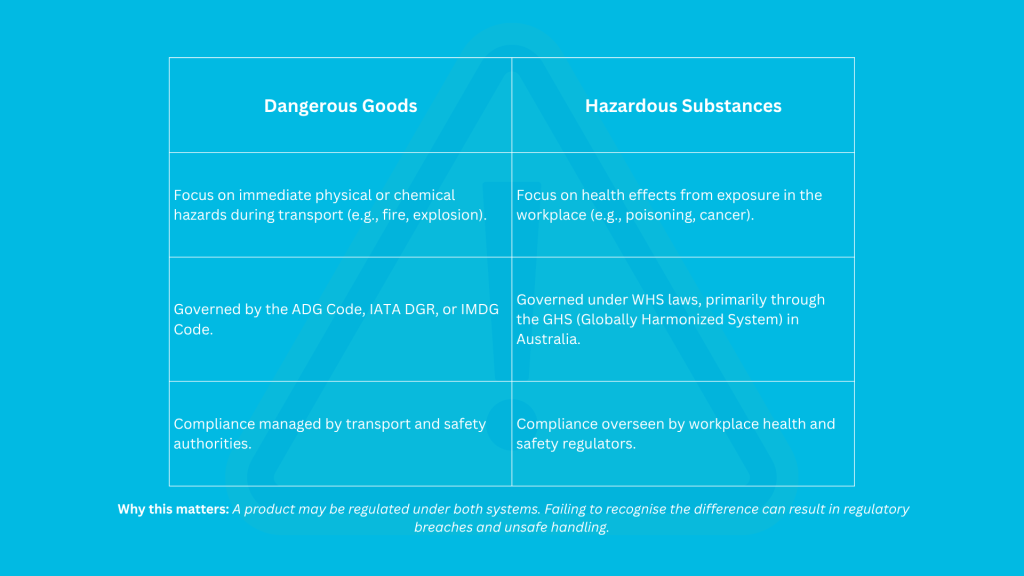

A Crucial Distinction: Dangerous Goods vs Hazardous Substances

Crucially, in Australia, it’s vital to grasp the distinction between “hazardous substances” and “dangerous goods.” While both terms relate to inherent risks, they operate under different regulatory frameworks for different purposes.

Hazardous substances are primarily a concern for workplace health and safety (WHS). They focus on the health effects of exposure (e.g., toxicity, irritation) under the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). For instance, a cleaning product might be a hazardous substance due to its corrosive effect on skin.

Dangerous goods, conversely, focus on the immediate physical or chemical hazards during transport. For example, fire, explosion, or chemical reactions. The same corrosive cleaning product, therefore, becomes a dangerous good because of its potential to corrode transport containers or cause severe burns during a spill in transit. Many substances, in fact, fall under both categories, meaning they are regulated for both their workplace health risks and their transport safety hazards. Understanding this dual regulation is a cornerstone of comprehensive compliance for Australian businesses.

For a comprehensive overview of what constitutes dangerous goods and the overarching principles of their transport, we’ve prepared a detailed ‘Guide to Shipping Dangerous Goods‘.

Why Is Classification & Labelling So Essential?

The meticulous process of classifying and labelling dangerous goods isn’t just bureaucratic red tape. Also it’s the very foundation of safe and efficient transport.

- Firstly, and most importantly, it’s about safety. Accurate classification ensures that potential hazards – be it the risk of fire, explosion, corrosion, or toxicity – are clearly identified and communicated. This protects everyone involved: the workers handling the goods, emergency responders in the event of an incident, and the wider public.

- Secondly, it’s about compliance and avoiding severe legal obligations. Australia, like the rest of the world, has stringent laws governing dangerous goods. As a result failure to correctly classify, package, or label goods can lead to hefty legal penalties. Additionally it could lead to significant fines, customs seizures, and even imprisonment in severe cases. So such non-compliance inevitably leads to costly business disruptions, tarnishing your reputation and potentially impacting your ability to trade.

- Additionally, proper classification and labelling drive operational efficiency. When dangerous goods are correctly identified, they can be handled, packaged, and stowed appropriately. Consiquently it ensures smooth customs clearance and preventing costly transport delays. Without this clarity, shipments can be held up indefinitely.

- Finally, it’s absolutely vital for emergency preparedness. In the unfortunate event of an incident, accurate labels and documentation provide critical, immediate information to emergency responders. As a result it enables them to take appropriate action, minimise harm, and contain the situation effectively.

Key Australian Regulatory Framework: A Multi-Modal Landscape

In Australia, the transport of dangerous goods is governed by a robust framework designed to harmonise with international standards.

- Australian Dangerous Goods (ADG) Code.

Firstly, the ADG stands as the primary national regulation, specifically setting out the requirements for the safe transport of dangerous goods by road and rail.

It contains:

- Classification criteria

- A comprehensive Dangerous Goods List

- Detailed instructions on packaging, labelling, and segregation

- Special provisions and exemptions

It’s important to understand that the ADG Code isn’t a standalone law. Instead, its legal force comes from being adopted and enforced through specific dangerous goods transport laws in each Australian state and territory.

Moreover, the latest edition of the Australian Dangerous Goods (ADG) Code is Edition 7.9. It can be used from 1 October 2024 and becomes mandatory from 1 October 2025.

- United Nations Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods (Model Regulations).

Secondly, Australia’s regulations are closely aligned with the UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods (Model Regulations), often referred to as the “Orange Book.” Generally, this alignment ensures consistency across different modes of transport globally. For businesses engaging in international trade, it’s crucial to also be aware of the mode-specific international codes:

- IMDG Code (International Maritime Dangerous Goods).

Thirdly, the IMDG Code (International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code) governs dangerous goods transported by sea freight.

- IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR).

The IATA DGR (International Air Transport Association Dangerous Goods Regulations) sets the rules for dangerous goods transported by air freight, which are based on the ICAO Technical Instructions (International Civil Aviation Organization).

Demystifying Hazardous Goods Classification: The "What," "How," and "Who"

Once you grasp what dangerous goods are, the next critical step is understanding how they are classified. This process is far from arbitrary; instead, it’s a meticulously defined system designed to ensure global consistency and safety.

What is Hazard Classification?

At its core, hazard classification is the systematic process of identifying the inherent hazardous properties of a substance or article. Subsequently, it involves assigning that item to the correct dangerous goods class (and often a specific division) based on internationally agreed criteria. Think of it as giving a hazardous item its unique, universal identity for transport purposes. Ultimately, this classification dictates every subsequent aspect of its journey: from the specific type of packaging required, to the labels it must display, the documentation that must accompany it, how it’s stowed and segregated from other goods, and crucially, how emergency responders would handle an incident.

Moreover, it’s important to understand the direct connection between dangerous goods classification for transport and the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). GHS, specifically GHS 7, is now mandatory for all Australian jurisdictions for classifying and labelling chemicals in the workplace. While GHS primarily focuses on health and physical hazards for workplace safety, its hazard classifications often directly inform the dangerous goods classification required for transport. This is particularly true for substances that present both workplace health risks and immediate physical or chemical hazards during transit. Therefore, a chemical’s GHS classification is frequently your essential starting point for determining its dangerous goods classification.

How are Dangerous Goods Classified in Australia?

The Shipper's Responsibility

Firstly, it’s vital to understand that the shipper or consignor holds the primary legal responsibility for ensuring dangerous goods are correctly classified. In other words, if you’re offering goods for transport, you must make sure they are properly identified and documented.

The Hazardous Goods Classification Process – Step-by-Step

The classification process follows a logical and regulated structure:

1. Gathering Information

Firstly, the foundation of accurate classification relies heavily on reliable data. Foremost among these sources are Safety Data Sheets (SDS), which have replaced the older Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS). An SDS is a detailed document providing comprehensive information about a hazardous chemical. Specifically, for dangerous goods classification, you’ll find critical information in Section 14 (“Transport Information”) of the SDS. This section typically provides the substance’s UN Number, its Proper Shipping Name, its Hazard Class, and often its Packing Group, along with any special provisions. Additionally, technical data sheets, product formulations, and manufacturer specifications are invaluable sources of information.

2. Applying the Classification Criteria

Secondly, classification is never a guesswork exercise. Instead, it involves rigorously comparing the known properties of your substance or article against the specific classification criteria detailed within the relevant dangerous goods codes. For road and rail transport in Australia, these criteria are found within the Australian Dangerous Goods (ADG) Code. For example, a liquid’s flash point is a key criterion for determining if it’s a flammable liquid (Class 3), just as a substance’s pH level can determine if it’s a corrosive substance (Class 8).

3. Testing (When Necessary)

Thirdly, while an SDS often provides sufficient information for known substances, new chemicals, novel mixtures, or complex articles may require specific testing to determine their precise hazard properties. In such instances, engaging specialist laboratories certified to conduct these tests is essential to ensure accurate classification.

4. Mixtures & Solutions

Moreover, when dealing with mixtures, the approach to classification can vary. Ideally, the mixture itself is tested to determine its overall hazardous properties. However, if testing isn’t feasible, classification can often be done by applying calculation methods based on the known hazards and concentrations of its individual components. For instance, the flammability or corrosivity of a mixture can be assessed based on the properties of its ingredients.

5. Assigning Key Identifiers

Once the classification process is complete, you will arrive at the crucial identifiers that define your dangerous good for transport. These include:

- The Proper Shipping Name (PSN): This is the official, internationally recognised technical name for the dangerous good (e.g., “UN 1203, PETROL, Class 3, PG II”). Using the correct PSN is non-negotiable.

- The UN Number: This is a unique, four-digit identification number assigned to specific dangerous goods (e.g., UN 1203 for petrol). It provides a rapid, universal identifier.

- The Hazard Class(es) and Division(s): This specifies the primary type of danger posed (e.g., Class 3 for flammable liquids) and any specific subdivisions within that class (e.g., Division 2.1 for flammable gases). Subsidiary risks, indicating additional significant hazards, must also be identified.

- The Packing Group (PG): This is assigned to certain dangerous goods classes (specifically Classes 3, 4, 5.1, 6.1, 8, and some of Class 9) and indicates the degree of danger. For example, Packing Group I signifies high danger, Packing Group II medium danger, and Packing Group III low danger. Importantly, this group directly dictates the strength and type of packaging required.

- Special Provisions: These are specific conditions or exemptions that may apply to a particular UN entry, offering additional guidance or requirements.

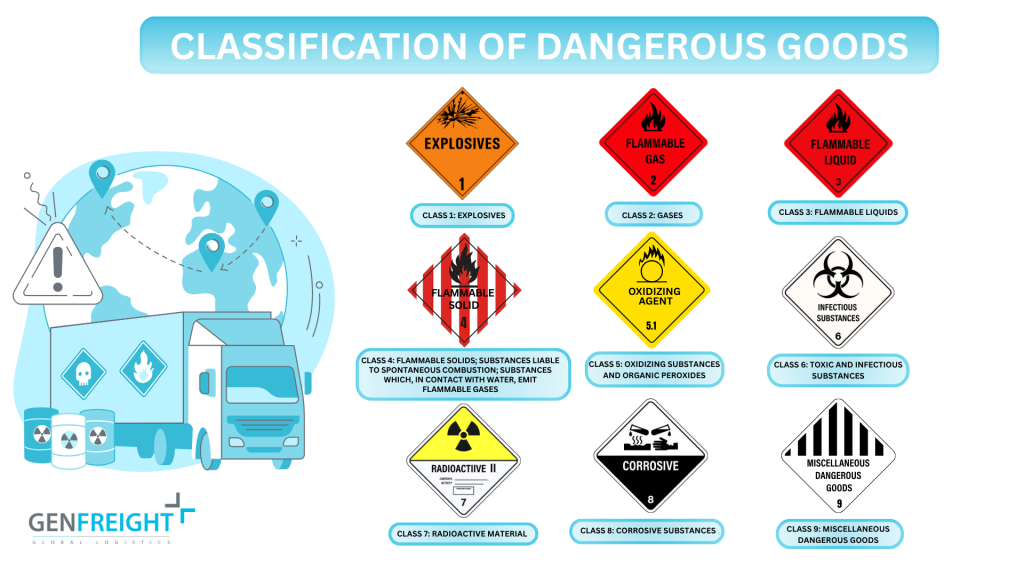

The 9 Classes of Dangerous Goods: A Comprehensive Breakdown

To begin with, dangerous goods are divided into nine UN hazard classes, which are universally recognised in transport regulations worldwide.

Each class represents a different type of physical or chemical hazard, such as flammability, toxicity, or reactivity.

Importantly, several of these classes are further divided into subdivisions (called divisions) to indicate more specific hazard types.

Understanding these classifications is critical for safe packaging, labelling, and handling—especially in Australia’s complex regulatory environment.

Class 1: Explosives

- General Hazard: Explosives are substances or articles that can, by chemical reaction, produce gases. Typically, these gases are generated at such high temperature and pressure, and with such speed, that they cause damage to the surroundings. Essentially, they pose a risk of explosion.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions: This class is highly complex; therefore, it features six key divisions based on the primary hazard:

- 1.1 Mass explosion hazard: This involves almost the entire load instantaneously.

- 1.2 Projection hazard: Here, the danger comes from flying fragments, but not a mass explosion.

- 1.3 Fire hazard with minor blast or projection hazard: Consequently, a fire could cause minor explosions or projections.

- 1.4 No significant hazard: This division represents a relatively low risk, often used for consumer fireworks.

- 1.5 Very insensitive with mass explosion hazard: Such substances are extremely difficult to detonate, however, they are still capable of a mass explosion.

- 1.6 Extremely insensitive with no mass explosion hazard: Ultimately, this presents a very low risk of accidental detonation.

- Common Australian Examples: This includes items like fireworks (various divisions), blasting caps commonly used in mining, different types of ammunition for sporting or defence, and detonators.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: The primary risks are catastrophic explosions, which can lead to severe structural damage, widespread destruction, and significant fatalities or injuries. Consequently, handling these requires highly specialised training and equipment.

- Label Pictogram: This label is typically orange, featuring an exploding bomb symbol in black, along with the class number “1” at the bottom.

Class 2: Gases

- General Hazard: Gases are substances that are entirely gaseous at 20°C and standard pressure, or that have a critical temperature of 50°C or less. Furthermore, they can be flammable, non-flammable/non-toxic, or toxic, and thus pose risks from pressure, cold burns, or chemical properties.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions:

- 2.1 Flammable Gases: These ignite easily when mixed with air.

- 2.2 Non-flammable, Non-toxic Gases: These pose no immediate fire or toxicity risk; however, they can be asphyxiating or cause extreme cold burns.

- 2.3 Toxic Gases: Importantly, these can cause death or severe injury to humans if inhaled.

- Common Australian Examples: This class includes LPG cylinders for BBQs or heating, acetylene commonly used in welding, aerosol cans (such as hairspray, deodorants, or spray paints), oxygen cylinders for medical or industrial use, and even helium balloons for party supplies.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: Risks include explosions from flammable gases, asphyxiation from non-toxic gases displacing oxygen. Moreover, the risks are severe cold burns from cryogenic gases, and poisoning from toxic gases. Therefore, proper ventilation and cylinder integrity are critical for safe transport.

- Label Pictogram:

- 2.1 Flammable: This label is red, with a flame symbol in black or white, and the number “2”.

- 2.2 Non-flammable, Non-toxic: This label is green, with a gas cylinder symbol in black or white, and the number “2”.

- 2.3 Toxic: This label is white, with a skull and crossbones symbol in black, and the number “2”.

Class 3: Flammable Liquids

- General Hazard: Firstly, flammable liquids are liquids—or liquids containing solids in solution or suspension—that can emit flammable vapours. Additionally, these vapours are released at relatively low temperatures, known as the flash point. Consequently, they pose a significant fire risk.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions: There are no divisions within Class 3. However, substances are assigned a Packing Group (PG I, II, or III) based on their flash point and boiling point, thereby indicating the degree of danger.

- Common Australian Examples: This class is very common in Australian commerce, including petrol (gasoline), various paints, varnishes, solvents (like paint thinners, acetone), ethanol, methanol, many types of perfumes, aftershaves, and hand sanitizers.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: The primary danger is fire, which can spread rapidly. Furthermore, vapours can also ignite explosively. Therefore, storage requires excellent ventilation and stringent ignition source control.

- Label Pictogram: This label is red, with a flame symbol in black or white, and the class number “3” at the bottom.

Class 4: Flammable Solids; Substances Liable to Spontaneous Combustion; Substances Which, in Contact with Water, Emit Flammable Gases

- General Hazard: This class covers solids and substances that exhibit flammability or reactivity under specific conditions.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions:

- 4.1 Flammable Solids, Self-reactive Substances, and Solid Desensitized Explosives: These are readily combustible, or can cause fire through friction, or are inherently unstable.

- 4.2 Substances Liable to Spontaneous Combustion: These substances can ignite spontaneously under normal transport conditions without an external heat source.

- 4.3 Substances Which, in Contact with Water, Emit Flammable Gases: These react dangerously with water to produce flammable gases, which can then form explosive mixtures with air.

- Common Australian Examples:

- 4.1: This includes matches, sulfur, certain metal powders (e.g., aluminium powder), and fibres soaked in oil.

- 4.2: Examples here include carbon (activated carbon), white phosphorus, and certain types of fishmeal.

- 4.3: Notably, this includes calcium carbide (used for acetylene generation), sodium, and potassium.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: Risks include rapid fires, self-ignition, or the generation of explosive gas mixtures. Consequently, proper ventilation and protection from moisture are crucial depending on the specific division.

- Label Pictogram:

- 4.1: This label is white with seven vertical red stripes, a flame symbol in black, and the number “4”.

- 4.2: This label features an upper half that is white and a lower half that is red, with a flame symbol in black, and the number “4”.

- 4.3: This label is blue, with a flame symbol in black or white, and the number “4”.

Class 5: Oxidizing Substances and Organic Peroxides

- General Hazard: These substances can either cause or contribute to the combustion of other material. Or they are thermally unstable substances that can undergo exothermic self-accelerating decomposition.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions:

- 5.1 Oxidizing Substances: These are not necessarily combustible themselves; however, they can yield oxygen, which ultimately causes or contributes to the combustion of other material.

- 5.2 Organic Peroxides: These are thermally unstable organic compounds that can undergo exothermic self-accelerating decomposition. Furthermore, they can be sensitive to impact or friction.

- Common Australian Examples:

- 5.1: This includes ammonium nitrate (a common fertiliser, often implicated in large-scale explosions if mishandled), high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, and calcium hypochlorite (pool chlorine).

- 5.2: Examples here include certain types of fibreglass resins, hardeners, MEK peroxides, and some bleaching agents.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: Risks include intensifying fires (oxidizers make fires burn hotter and faster), self-accelerating decomposition (organic peroxides), and explosions. Therefore, segregation from flammable materials is vital.

- Label Pictogram:

- 5.1: This label is yellow, with a flame over a circle symbol in black, and the number “5.1”.

- 5.2: This label is also yellow, with a flame over a circle symbol in black, and the number “5.2”.

Class 6: Toxic and Infectious Substances

- General Hazard: These substances are liable to cause death or serious injury or to harm human health if swallowed, inhaled, or by skin contact (toxic). Alternatively, they are substances known or reasonably expected to contain pathogens (infectious).

- Key Characteristics/Divisions:

- 6.1 Toxic Substances: These substances can cause serious illness or death through ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact.

- 6.2 Infectious Substances: These substances contain pathogens that can cause disease in humans or animals.

- Common Australian Examples:

- 6.1: This includes many pesticides and insecticides, cyanide compounds, certain cleaners or disinfectants, and some laboratory chemicals.

- 6.2: Examples here include clinical waste from hospitals, pathology samples, diagnostic specimens, and biological cultures.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: The dangers involve direct poisoning, disease transmission, and widespread contamination. Consequently, strict handling procedures, appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), and leak-proof packaging are essential.

- Label Pictogram:

- 6.1: This label is white, with a skull and crossbones symbol in black, and the number “6”.

- 6.2: This label is white, with a three-crescent symbol over a circle (biohazard symbol) in black, and the number “6”.

Class 7: Radioactive Material

- General Hazard: This class covers any material containing radionuclides where both the activity concentration and the total activity in the consignment exceed specified values. Ultimately, they emit ionising radiation.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions: Generally, there are no specific divisions for Class 7. However, categories are defined by the level of radiation and the transport index (e.g., Category I-White, II-Yellow, III-Yellow).

- Common Australian Examples: This includes medical isotopes used in diagnostic imaging or cancer treatment, certain industrial gauges, and uranium yellowcake, which is a crucial product from uranium mining operations.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: Exposure to radiation can cause tissue damage, illness, or genetic mutations. Consequently, strict shielding, time limits for exposure, and maintaining distance from the source are paramount. Such materials require highly specialised handling and transport protocols.

- Label Pictogram: This label features a white upper half and a yellow lower half, with a black trefoil symbol (radiation symbol) and the word “RADIOACTIVE,” plus the class number “7” at the bottom. Furthermore, the specific category (I, II, III) and content are usually indicated directly on the label.

Class 8: Corrosive Substances

- General Hazard: These are substances that, by chemical action, will cause severe damage when in contact with living tissue. Alternatively, they will materially damage, or even destroy, other freight or the means of transport.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions: There are no specific divisions for Class 8. However, substances are assigned a Packing Group (PG I, II, or III) based on the severity of their corrosive effect.

- Common Australian Examples: This class is widely encountered, including battery acid (sulfuric acid), caustic soda (sodium hydroxide), hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, many drain cleaners, and some concentrated industrial cleaning products.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: These pose dangers of severe burns to skin and eyes, and can damage respiratory tracts if inhaled. Additionally, they can corrode metals and other materials. Therefore, robust, corrosion-resistant packaging and effective spill containment measures are crucial.

- Label Pictogram: This label features an upper half that is white and a lower half that is black, with liquids pouring from two test tubes onto a hand and a metal block symbol in black, and the class number “8”.

Class 9: Miscellaneous Dangerous Goods

- General Hazard: This broad class covers substances and articles that during transport present a danger not covered by the other classes.

- Key Characteristics/Divisions: There are no formal divisions within Class 9. Nevertheless, the class is broad and encompasses a variety of hazards.

- Common Australian Examples: This is a very broad and increasingly important class, particularly for Australian businesses. Key examples include:

- Lithium Batteries: This is arguably the most significant item in Class 9, covering lithium-ion batteries (found in phones, laptops, power tools, electric vehicles) and lithium metal batteries. Due to their inherent fire risk if damaged or short-circuited, they have very specific and stringent transport requirements.

- Dry Ice (Solid Carbon Dioxide): This poses risks of asphyxiation (due to displacing oxygen) and extreme cold burns.

- Magnetised Materials: These can interfere with aircraft navigation systems.

- Asbestos: This material is hazardous due to its carcinogenic properties.

- Environmentally Hazardous Substances: These are substances that are hazardous to aquatic environments, even if not classified under other primary hazards.

- Capacitors: These may store an electrical charge.

- Associated Risks & Safety Considerations: Risks vary greatly depending on the specific item. They can range from fire (lithium batteries), to asphyxiation (dry ice), navigational interference (magnetised materials), or long-term health effects (asbestos). Consequently, specific handling and packaging requirements are essential for each particular type.

- Label Pictogram: This label is white, with seven vertical black stripes in the upper half, and the class number “9” at the bottom.

Labelling & Placarding Requirements

Once dangerous goods are carefully sorted and identified, the next vital step involves clearly showing their dangers to everyone who might handle them during transport. This is exactly where labels and placards become essential. Indeed, dangerous goods labels act as universal visual signs that immediately tell handlers, transporters, and emergency workers about the risks, no matter what language they speak.

Key Elements of a Dangerous Goods Label (for packages)

For individual packages holding dangerous goods, putting on the right labels is a must. These labels have to clearly and consistently show specific details to keep things safe and legal:

- Class Diamond (Picture Symbol): This is the easiest part to spot. It’s a standard diamond shape, usually at least 100x100mm, with special colours and symbols for each type of danger, thereby indicating the main hazard.

- Essential Identification: In addition, key information like the Class Number, the unique UN Number, and the Proper Shipping Name (PSN) must be clearly printed on the package.

- Extra Markings: What’s more, depending on the goods, labels might also need to include Subsidiary Risk Labels for other dangers, Direction Arrows for liquids, and an Overpack Label if several smaller packages are put into one larger outer box.

Placarding (for transport units)

While labels go on single packages, placards are much bigger, more noticeable signs (at least 250x250mm). These are required on transport units like trucks, trains, shipping containers, and tanks. The main reason for placards is to instantly show the biggest danger (or dangers) of the whole load inside the transport unit.

For example:

- Road and Rail (ADG Code): Trucks and rail wagons carrying dangerous goods must display placards and, for bulk loads, Emergency Information Panels (EIPs). These EIPs show the UN Number, PSN, Hazchem Code, and emergency contact details. Importantly, ADG Code Edition 7.9 proposes changes for EIPs on Intermediate Bulk Containers (IBCs), aiming for better international alignment.

- Sea (IMDG Code): Freight containers used for sea transport also need placards on their sides. Generally it’s necessary for communication the hazards of the cargo inside, following the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code.

- Air (IATA DGR): Air cargo generally relies on detailed package labelling and documentation rather than large placards on the aircraft itself, due to the unique safety considerations of air transport.

Australian Specifics & Good Practices for Labelling

Beyond the worldwide rules, Australian guidelines offer particular advice and good practices for labels and placards.

- Firstly, it’s essential to look at the ANZ-ERG (Australian and New Zealand Emergency Response Guidebook). The 2024 Edition is now available; however, it’s key to remember that both the 2024 and 2021 editions are valid to use while ADG 7.9 is in effect. Still, older versions, such as the 2018 edition, are no longer allowed and must be replaced by businesses.

- Secondly, always make sure labels are strong, easy to read, and clearly visible on the outside of packages.

- What’s more, a vital good practice involves always removing or completely covering up old labels from packaging that’s being reused.

- Lastly, while strict rules generally apply, keep in mind that there are special allowances for limited quantities (LQ) and excepted quantities (EQ) of dangerous goods. In these cases, the labelling and paperwork rules might be less strict, but you still need to put specific marks on the packages.

Beyond Classification & Labelling: Holistic Compliance for Australian Businesses

Proper classification and labelling are only the beginning. Therefore, Australian businesses must also ensure full compliance across every stage of dangerous goods handling and transport.

Shipper's Broader Responsibilities

Importantly, consignors have legal duties that go far beyond assigning the correct hazard class.

- Correct Packaging. Firstly, businesses must use UN-certified packaging appropriate for the product type and Packing Group. This includes drums, boxes, IBCs, and gas cylinders, each serving a specific containment need.

- Proper Stowage & Segregation. Secondly, dangerous goods must be stored and transported in a way that prevents incompatible substances from reacting. This applies both within a container and at depots or ports.

- Accurate Documentation:

- Shipper’s Declaration. Firstly, this mandatory document confirms that dangerous goods are properly prepared and declared. Accuracy is non-negotiable. (See our full guide: The Dangerous Goods Declaration Process)

- Safety Data Sheets (SDS). Furthermore, these must accompany goods throughout the supply chain and remain accessible. They contain essential details on hazard control, emergency procedures, and safe handling.

- Supporting Documents. Additionally, depending on the mode of transport, documents may include manifests, container packing certificates (for sea freight), airway bills (for air), and customs declarations.

Training & Competency: A Legal Obligation

Moreover, all personnel involved in dangerous goods logistics must be trained and deemed competent.

- Firstly, under the ADG Code and related international rules (e.g., IATA DGR for air), training is legally required.

- Secondly, staff must understand their specific responsibilities—whether they pack, handle, transport, or manage documentation.

- Additionally, training must be regularly refreshed to keep up with regulatory updates.

Emergency Preparedness & Response

Furthermore, businesses must have effective emergency plans and access to vital response resources.

- The ANZ-ERG 2024 is a go-to emergency guide in Australia and New Zealand. It helps first responders take immediate, informed actions during incidents.

- The Hazchem Code also plays a crucial role, offering quick-reference instructions for spill containment, firefighting, and required PPE.

Continuous Improvement & Auditing

Finally, maintaining compliance is an ongoing process, not a one-off task.

- Conduct internal audits to identify gaps in dangerous goods handling.

- For complex situations or unclear classifications, engaging a dangerous goods consultant is highly recommended.

Conclusion

In wrapping up, it’s clear that accurate classification and precise labelling form the absolute cornerstone of safe and compliant dangerous goods transport. We’ve certainly highlighted how essential it is to understand hazardous goods classification, distinguishing between “dangerous goods” and “hazardous substances.”

For a seamless and compliant shipping experience, consider reaching out to GenFreight. As experts in global shipping , we handle dangerous goods with precision and care, provide essential customs clearance services, and much more, allowing you to focus on your core business with peace of mind.